Based in Fukushima, Kazuya Yokoe—also known as Kazuya Men—is the founder of MANWHO. Cherishing time with friends above all else, he has captured the local atmosphere and the charm of the people through his videos. Marking a milestone with his latest work, Kono 10 Nen (These 10 Years), we spoke with him about his journey so far and what lies ahead.

──MANWHO: KAZUYA YOKOE (ENGLISH)

[ JAPANESE / ENGLISH ]

Photos courtesy of Masa

VHSMAG (V): Let’s start with how you first got into making skate videos.

Kazuya Yokoe (K): At first, I bought a small HD handycam just to document little trips with my friends. It was more about making fun memory clips together. Back then, I was living in Koriyama for work, but I got transferred to Sendai, and that’s when I started filming more seriously. I’ve always had a lot of favorite skate videos, but LENZ by TIGHTBOOTH hit me in a way nothing else had before. It made me think, “I want to do something cool too.” The way they turned skating into a full-on creative statement, the attitude of capturing something lasting through video, even just the image of someone holding a VX—everything about it felt powerful. In Sendai, there was Maru and Bridge, and their presence really pushed me further toward filming. I remember him saying, “Being a filmer comes with its own drama.” There were always skaters out in the streets and I’d go up to them and say, “Let me film you—let’s make a local video.” That’s how it all started.

V: When was that?

K: That was 2014.

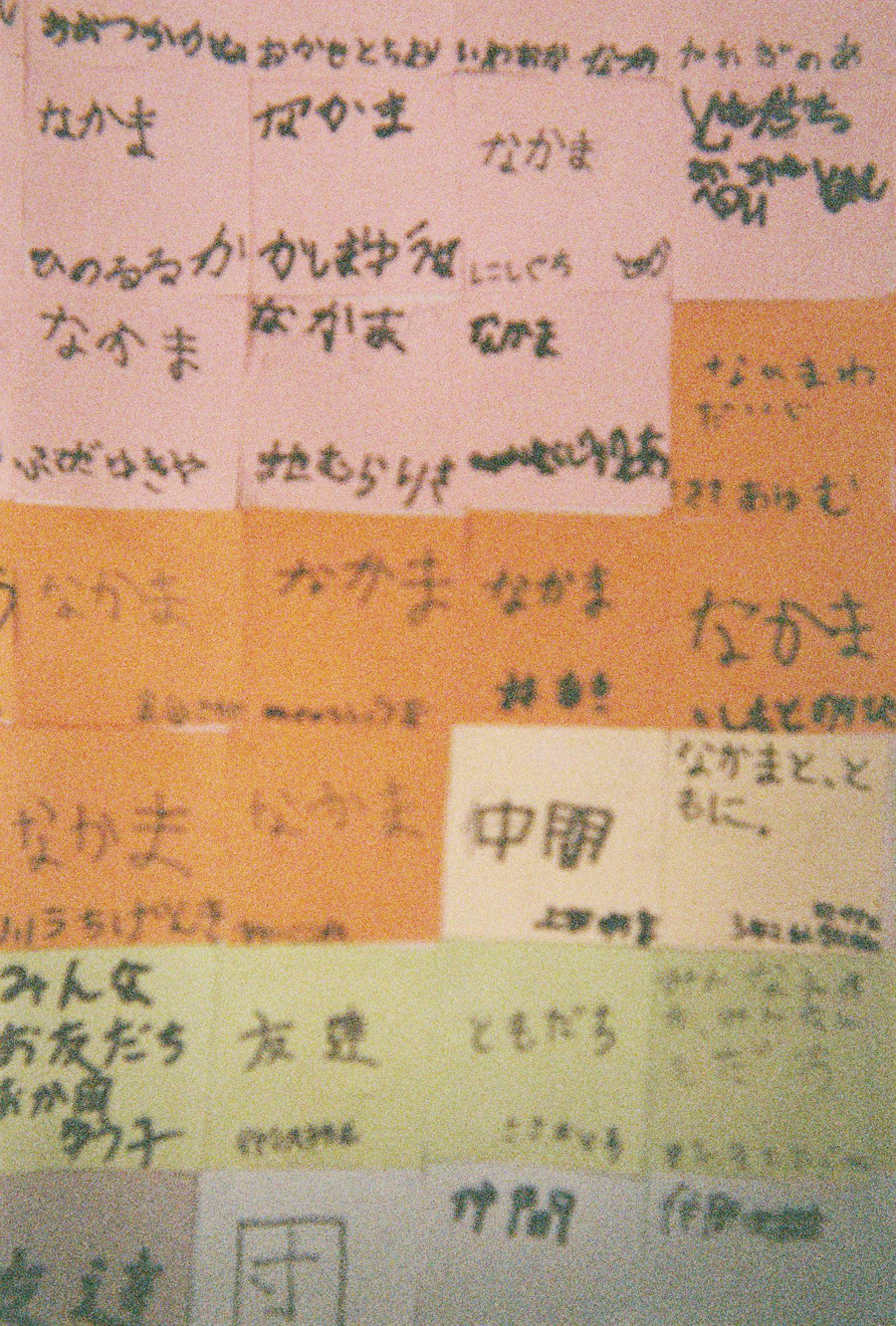

V: So this latest work, Kono 10 Nen, looks back on your entire career. Tell us about the name MANWHO—where does it come from, and what’s the meaning behind the concept of “a gathering of ten thousand winds, flowing freely”?

K: I’m the one who mainly makes the videos, but I have a creative partner who handles the graphics. He’s an artist named Syunoven, based in Sendai. He’s originally from Aizuwakamatsu in Fukushima, but we met after I moved to Sendai. From the very beginning, he’s been someone I could bounce ideas off of, and he’s been helping with the graphics ever since. When we were choosing music for one of our early videos, we came across a track called The Man Who by the band Jean-Michel Basquiat was part of. At the time, we still didn’t have a name for the production. But I really liked the way “MANWHO” looked written out—it had a nice ring to it, and “MAMWHO” was fun and easy to say aloud. It also contains the word “MAN,” which made me think: this is going to be a skate video that really reflects who each skater is as a human being. It wasn’t something we overthought or forced—it felt more like something that was already there, waiting for us to notice. Later, we realized we could write it in kanji too. “Man” (万) as in “ten thousand,” and “Who” (風) meaning “wind”—together suggesting a variety of skaters, each bringing their own wind or energy to the project. That’s how the concept of “a gathering of ten thousand winds, flowing freely” came about. It’s less of a crew or team, and more of a loose, open collective—people coming together naturally.

V: So through that kind of organic process, you connected with all sorts of skaters over the years. I heard that Uwasa, the space you ran for five and a half years, recently closed. It seemed like a really important spot for the local skate community—but what did that space mean to you personally?

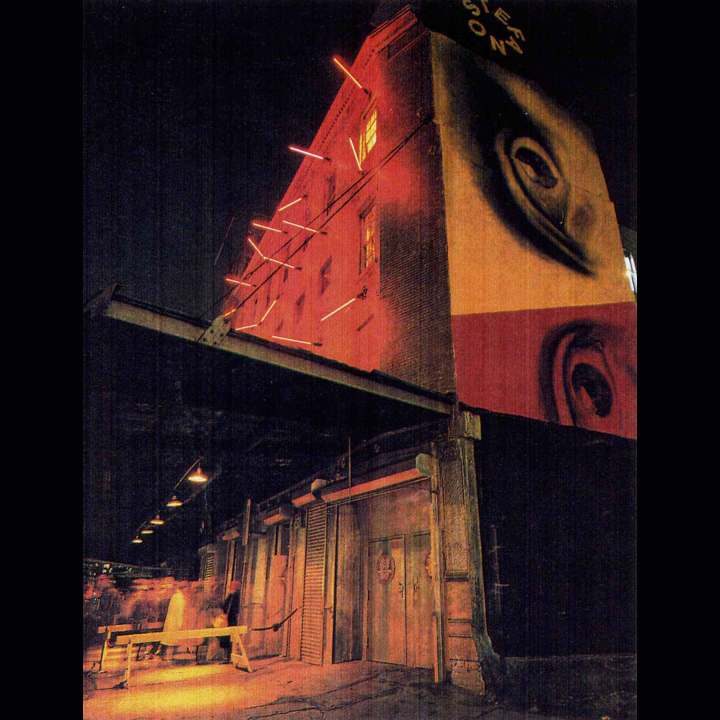

K: What I really wanted to create with Uwasa was a physical space where people could actually experience the world of MANWHO. Up until then, I think most people only knew MANWHO through the videos—but I felt it was important for us to connect face-to-face, to have real conversations, to let people feel what we’re about and to be influenced by each other in return. That space—the look and feel of the town, the atmosphere of the building—held so much of what we value. The quiet beauty of things fading with time, for instance. More than anything, Uwasa was a place where people could directly connect to the big circle MANWHO had brought together. That’s why the most important thing for me about the space was the human interaction—the kind of exchange that can only happen through in-person communication, not just through a screen. I ended up talking with people all the time there. Toward the end, we’d crash upstairs with the skaters who always dropped by, all sleeping together packed into the room. It was a small corner of a small town, but having a place in the city that felt like our own safe haven—there was something deeply meaningful about that.

V: During those five and a half years at Uwasa, are there any particular moments or relationships that have stayed especially close to your heart?

K: There are so many memories that it’s hard to pick just one... but what stands out the most is the people who came all the way from far away just to visit Uwasa. Sometimes they’d travel for hours by scooter or car, aiming specifically for that spot. Their dedication gave me a lot of energy, and I still clearly remember all their faces. Every moment of vibe and energy exchanged there stays close to my heart. Interestingly, quite a few visitors weren’t even skaters—photographers, musicians, painters, and others who were either expressing themselves or wanting to. Meeting so many creative people like that was really inspiring and something I’m grateful for. Above all, what stays with me most is how Uwasa was peacefully embraced by everyone around Shinmachi Building Street—from the snack bar owners to the local neighbors. Being able to open and run Uwasa in that calm, everyday environment means a lot to me.

V: How did the video project Kono 10 Nen, which looks back over your career, get started?

K: My previous work, Manwhojin (万風神), released in 2023, was something I put my heart and soul into. After that, I spent some time focusing on running the shop and being with my family, watching and thinking about what to film next. Then, in 2024, I suddenly realized, “This is the 10th year.” That sparked a strong urge to get moving again. I wanted to test how far I’d grown over this decade. Being a filmer has given me so much, so I naturally felt the desire to create a video expressing my gratitude for all that time. That’s how I found myself hitting the road again.

V: I see. So it’s kind of about looking back over the past 10 years and expressing the connections and experience you’ve built up through new clips, right?

K: Exactly. And it’s not just about my ten years—it’s also MANWHO’s ten years. For example, Kojiro Hara, who I filmed a part with for this project, has been a close friend for a decade. I wanted this to be a piece that reflects on the ten-year journeys of everyone involved. It’s something I made to mark a turning point—not just in my own life, but in the lives of my friends as well.

V: Watching it, I really felt how close you are to the people you’re filming. Since it’s made entirely with your friends, the whole 40 minutes feels so genuine—it’s a really comfortable piece to watch. When it came to filming and editing, was there anything you decided on from the start or a core idea you never strayed from?

K: There was a rough time frame I wanted to finish it by, so I knew I didn’t have enough time to take the usual approach of filming a wide range of skaters. That’s why I first asked myself, What’s the most important thing here? And the answer was: to prioritize the time I spend with the skaters I’m filming full parts with. Iori Fukuma is in Fukuoka, Taizo Muku is in Osaka, and Kojiro is in Kobe—so they’re all in different places. That meant it was on me to go see them. I poured all the time and energy I had into that. In the end, it was really about choosing to film the skaters who felt right to shoot at the time.

V: The skaters that had full parts in this video—of course they’ve got serious skills, but would you say the bigger factor was your personal connection with them? Did it naturally end up being people you have a deeper relationship with?

K: It’s not as simple as just saying, “They’re good people, so let’s film a part.” As a filmer, I do make a conscious decision when I point the camera at someone. These days, skating in the streets comes with increasing risks, so I think a skater’s ability to perform in those intense, momentary situations really matters too. And ultimately, the most important thing is that I’m a genuine fan of the person I’m filming. Even if they’re younger, I need to have respect for them and truly want to film their part. Feeling happy and excited while filming—that pure enjoyment—is what matters most. That’s what makes the whole process fun and what, I think, leads to something really interesting.

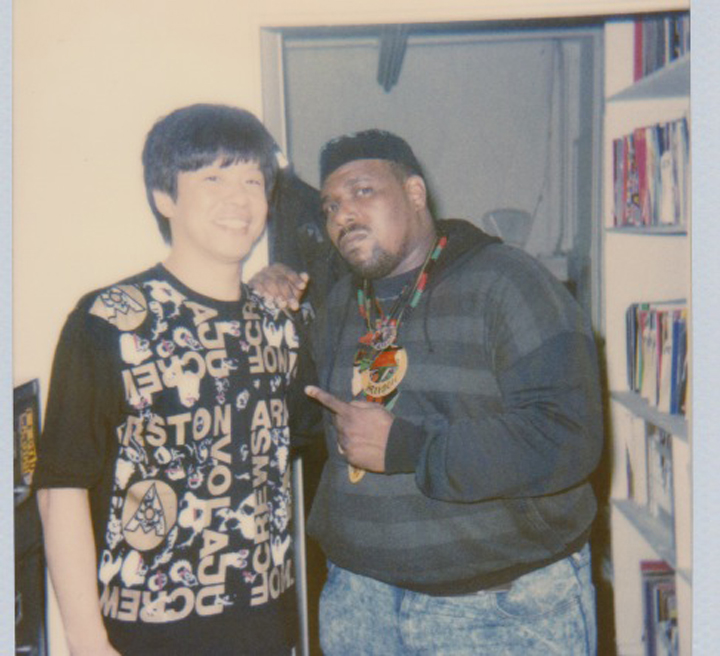

V: In terms of full parts, I thought it was pretty fresh to see a part featuring Masa, the photographer. That kind of approach felt really unique. I imagine it only came together like that because of the relationship you two have built over the years, right?

K: Yes. As I was thinking about the overall structure of the video, I started to feel that it was finally time for Masa to have his own part. We’ve been walking this path together for years, but I’d never really featured his photography in any of the footage before. With this project, I felt it was important to create a section where people could really feel what he captures and the atmosphere he brings. So we built that part together. Also, both Masa and I had a strong impression from that Strush video where they focused on Takayan—right after Daiki Hosoda’s part. That really stuck with us. It made us realize there’s still so much potential in using photography—like a slideshow—to create new forms of video expression.

V: How did you go about selecting the music for this project?

K: There’s this super talented DJ and skater named Masaru Mitarai who runs a record shop called RA’S DEN RECORDS down in Oita. He actually produced original tracks for MAN WHO 2, and from MAN WHO 3 onward, he’s played a major role in selecting the music. It’s not like he chooses every song, but he always sends me a bunch of tracks that he thinks would fit the MANWHO vibe. From there, I try laying them over the footage to see how they feel, or I’ll ask him for something with a slightly different mood. It’s always this steady, back-and-forth process we go through together. Sometimes I’ll swing by Oita while I’m on tour, just to hang out and catch up. He really gets what MANWHO is about—he understands my taste too—so having him involved is a huge help. Then Syunoven throws in ideas based on that foundation, and sometimes I’ll hear something and just know, “This part has to be this track, no question.” That’s the kind of flow we work in.

V: What kinds of things outside of skateboarding influence your approach to filmmaking and visual expression?

K: When I was little, I used to watch all kinds of films on shows like Kinyo Roadshow—you know, those classic Friday night movie programs on TV. Nowadays, I don’t really watch TV, so I’m not sure how things are these days, but back then, those Japanese films I saw on those programs left a lasting impression. That nostalgic feeling from my childhood memories is probably a big influence on what I’m expressing now. Even though I’m living in the present, I think I’m always searching for that blend of something new yet familiar—a kind of nostalgia. Just recently, I got my hands on a VHS copy of Mizu no Tabibito, a ’94 movie I remember watching on TV as a kid.

V: So it’s definitely Japanese films rather than overseas ones that influence you. MANWHO’s work feels deeply rooted in Japanese culture and aesthetics rather than an international vibe.

K: When I first started skating, I definitely had a fascination with America—I’d watch videos like Antihero’s Tent City at my friends’ houses and dream about that world. Of course, I admired the vibe of places like New York. But as I began filming and gaining experience myself, I realized why those skaters look so cool: it’s because they’re expressing their own “land” and their own “way of life” through their videos. If we’re going to show genuine respect for America and other countries, then we should express ourselves based on the places and cultures we grew up in. That way, both sides can acknowledge and appreciate the differences between us—that’s the ideal. Also, as a Japanese person living through these rapidly changing times, I feel a desire to digest and preserve the landscapes, culture, and sensibilities that have been cherished here. While searching for that sense of nostalgia, I’m trying to create work grounded in my own upbringing, experiences, and feelings. I think that’s the most honest way to express myself and communicate who I really am.

V: What do you want to convey through your videos, especially the feelings and message behind Kono 10 Nen?

K: The preciousness of life. Simply being alive is incredibly valuable. Over these past ten years, I’ve experienced losing friends, family, and things dear to me, which made me deeply realize that my own life is finite. Because of that, I strongly feel that I have to do what I want while I’m still alive—that drive has been my motivation for creating my work. It’s about keeping the flame of passion burning. I hope that feeling comes through in the videos. I’m not trying to explain things plainly or literally through the footage, but I want something to reach deep into the hearts of the viewers. I believe these videos will outlive me, and through them, my friends and I will continue living on. Holding onto that vision is why I put everything I have into making each video.

V: Recognizing that time is limited helps to shape your mindset and gives your direction a clearer focus.

K: I’m also aware that as a filmer, I have my limits. Of course, life itself is finite, and my body won’t keep moving the same way forever or let me shoot videos at the same quality. For example, if I were to injure my knee and couldn’t keep up with speed, things would definitely change. People change over time, and ultimately, we all face death. Keeping those changes in mind, I feel I have to choose what I can do now. In terms of direction, there’s also the “wind” of the world around me. Last year, I pushed hard and completed a project, but I also feel like I’m steering my path not just by my own will, but by reading and responding to bigger external forces.

V: In your Instagram post about Uwasa closing, you wrote something that really stuck with me: “To keep pursuing your ideals, you have to keep changing yourself.” What kind of ideal does MANWHO envision?

K: The ideal might be something like this: that everyone involved—including myself—finds joy in this one and only journey of life. That would be the best outcome. In our daily lives, I only want to do things that feel enjoyable and worth my time. It’s about having desires and continuously raising the bar on those desires. I believe that mindset naturally reflects in both the work I create and in skateboarding itself.

V: You mentioned on Instagram after finishing this project that you want to keep filming going forward. Does that mean Kono 10 Nen served as a way for you to reaffirm how you want to move ahead in the future?

K: Yes. While filming Kono 10 Nen, I wanted to reconnect with that initial burst of passion. Making skate videos is still what excites me the most. But I also feel I need to seriously think about what I want to do and how I spend my time. Continuing to make videos, running the shop the way I have, loving my friends and family—it’s become clear that there just isn’t enough time to do all that on my own anymore. So I decided to end the shop in its current form and aim for the next ideal version. The shop’s closing isn’t a sad story—it’s a next step I chose myself. Right now, I’m gradually expanding my vision while having fun, thinking about how to enjoy things more freely and creatively going forward.

V: Since you’re editing videos at home, that space is becoming a new place where the entire MANWHO world can be experienced.

K: I think that getting a glimpse of the atmosphere and daily life of the place where the work is created can deepen people’s understanding of the videos and the world they come from—there’s something special they can really feel from that.

V: What are the core values you prioritize in MANWHO’s work?

K: First and foremost, I just don’t do things I don’t want to do (laughs). But when something needs to be done, I do it sincerely. There are many things I value. For one, I couldn’t have kept going this far without my friends. A filmer alone can’t do anything—you can’t shoot without skaters. I’m grateful that there are skaters who make me passionate about creating videos. In that sense, the most important thing is living and working together with each individual skater and friend.

V: What are your thoughts on the current skate scene overall? Since the Olympics, there’s been more focus on the competitive side, but at the same time, it seems like the street scene is facing increasing restrictions… How do you see this situation?

K: I think skaters themselves have to think carefully and adapt as they move forward. Just continuing with the mindset of “I do it because it’s fun” isn’t enough anymore—especially as the environment around us changes, making things more challenging. So rather than stubbornly fighting against it, I feel the only option is to skillfully navigate those challenges and change ourselves. We have to be patient and low-key—I really don’t want to draw too much attention (laughs).

V: Do you feel a sense of meaning or mission in continuing your work based in your hometown of Fukushima after your time in Sendai?

K: For me, the biggest thing is that it feels comfortable—being here just suits me. But there’s definitely meaning in working from here. I’m not saying “the place you were born is always the best,” but every region has its own unique character, and I believe the environment you grow up in plays a big role in shaping who you are. Fukushima, surrounded by rich mountains and without the constant stimulation of a big city, is a place where living life at my own pace and making videos feels right. It’s not easy to create influence that draws people from other prefectures, but if we can stir things up ourselves and be one example of that potential, I’d be really happy. Also, some local skaters have started farming, creating things, or expressing themselves beyond just skating. I think that’s a result of what MANWHO values being expressed and conveyed through Uwasa. What we embodied in that place has, in some way, influenced how others live. That’s something I’m really glad about, and I believe it’s very meaningful.

V: That’s exactly why you’re able to create authentic work. Do you have any upcoming video projects planned?

K: To be honest, I don’t have anything concrete planned for upcoming projects yet. Sometimes when I’m drinking, I get excited about shooting another part with Kojiro or making a video about the local skaters from Uwasa back home. But nothing’s really in motion yet. At the same time, I’m curious to see how far I can push myself creatively with video. For example, I have a friend who runs a fishing lure brand—he’s originally a skater—and I went fishing with him to shoot some footage. When I uploaded clips to YouTube, he was really happy. So these days, I don’t feel like filming skateboarding is the only way I want to use my camera. Of course, making skate videos is still the main thing, but for instance, my kid loves trains, so sometimes we go film trains together, and then I come home and edit the footage with sounds. Creating those small stories is really fun too. That said, I don’t want to shoot just for money. It has to be because I want to do it. If that leads to recognition or opportunities, great—but I’ll never film just thinking, “This will make money.” I always want to keep that sense of excitement and playfulness alive in my work.

Kono 10 Nen

manwho.theshop.jp/items/105740289

Kazuya Yokoe

@manwhomono @kazuya_yokoe

Born in 1986 and based in Fukushima, he has spent the past decade creating under the name MANWHO, focusing on filmmaking and other creative pursuits rooted in his local community. Now, as he marks ten years of activity, he is moving toward a new chapter.