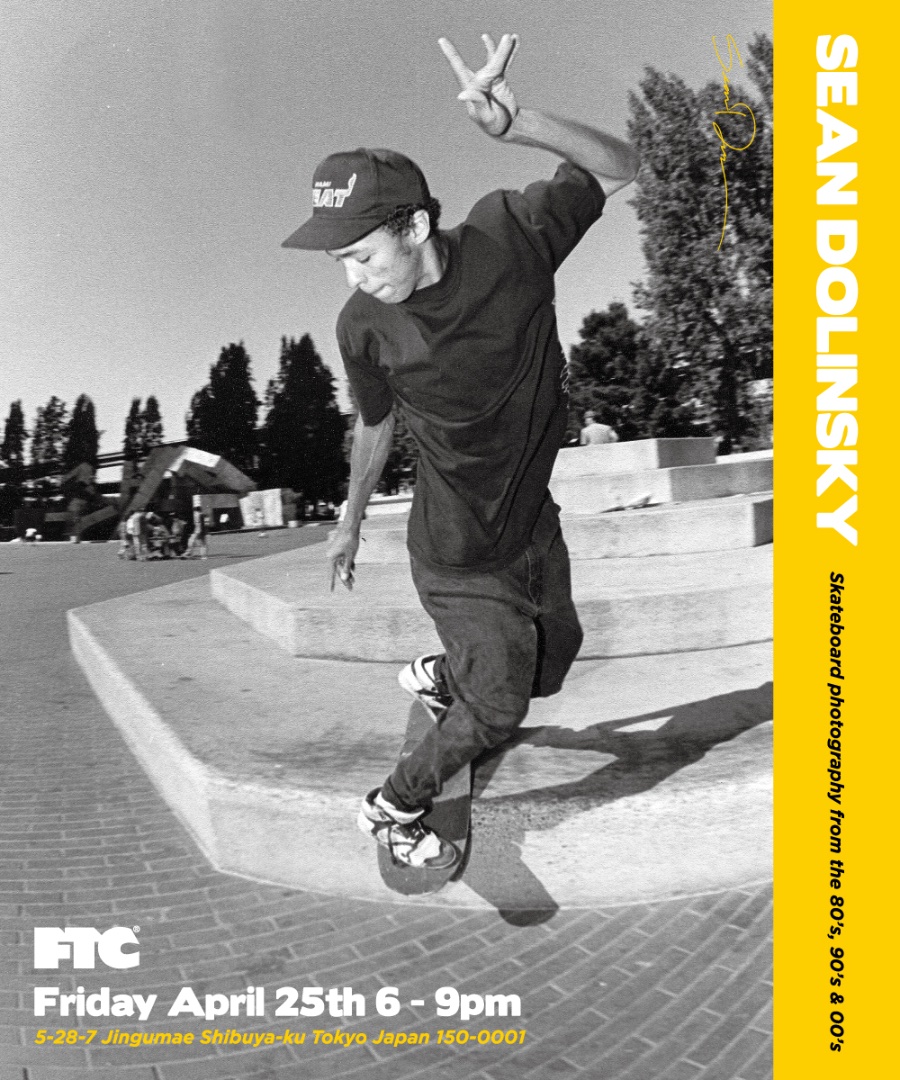

From the late 80s Powell Peralta era to the anarchic rise of World Industries in the 90s, Sean Cliver has stood at the heart of skateboarding’s most transformative moments. He entered the industry under the towering legacy of VCJ, plunged into the beautiful chaos of Steve Rocco’s universe, and today continues to challenge the very idea of skate art through his own label, StrangeLove Skateboards. During his visit to Japan for a solo exhibition celebrating Heshdawgs’ 20th anniversary, we had the chance to interview him. Here, he reflects on the early days of his career, the insanity of the ’90s, and his thoughts on the current landscape of skateboard graphics.

──SEAN CLIVER (ENGLISH)

[ JAPANESE / ENGLISH ]

Photos courtesy of Sean Cliver

Special thanks_Heshdawgs

VHSMAG (V): Do you remember the first time you picked up a skateboard? What drew you into that world in the first place?

Sean Cliver (S): Yes, it was the summer of 1986. My best friend had gotten into punk rock music through his older brother, and he picked up a cheap Taiwanese skateboard complete at a discount store. I thought it looked fun, so I bought a similar one at the same place… only to later discover that it was an embarrassing chunk of shit after finding my first copy of Thrasher Magazine. My friend soon got more into punk rock and stopped skating to start a band, but I fell in love with it. Especially once I realized there was a bike shop in our small Wisconsin town that sold professional quality skateboards, and I sold off some of my comic book collection to purchase my first real board: a Powell Peralta Mike McGill “Skull & Snake” model. From then on, I skated every day and made it my mission in life to learn how to ollie.

V: Before you ever worked in the industry, what kind of art or imagery spoke to you the most? Was there a particular magazine, board, or graphic that made you think, “I want to do this someday”?

S: I grew up wanting to be a comic book artist. I even made a little “mini-comix” that I sold through the mail for 25 cents when I was 15 years old. But once I set foot in a skate shop and took in all the board graphics surrounding me, I knew that was what I wanted to do. I wasn’t a great comic artist anyway, but drawing something for the bottom of a skateboard felt more like something I could possibly do. I was particularly inspired by the artwork on Powell Peralta, Santa Cruz, and Zorlac boards, and always preferred the illustrations by VCJ, Jim Phillips, and Pushead over any of the more graphic design-oriented boards at companies like Vision and Sims.

V: When you joined Powell Peralta in the late 80s, what kind of pressure or excitement did you feel stepping into that world of legendary graphics by VCJ?

S: I was terrified! Haha… when I had been flown out for the job interview in October 1988 to meet with George Powell, I went out to dinner with VCJ afterward and he’d told me he needed a break, that he was thinking about taking a sabbatical. So, when I finally found out that I got the job and started at Powell Peralta in January 1989, I was shocked to walk into the art department and discover that VCJ’s office was entirely gone. An empty workspace was all that remained. I thought I was going to be working underneath him, like an assistant or something… I had no idea I was supposed to fill his legendary shoes right away. So yeah, I felt a huge weight over my head, because I really didn’t want to go down in history as the guy who ruined Powell Peralta’s graphics. Although I’m sure some people may still think that. Haha…

V: You worked on Ray Barbee and Steve Saiz pro models. What was that like, since you could work from scratch?

S: The fact that both Ray and Steve were “blank slates,” so to speak, with no previous VCJ graphics, was a godsend. Especially Ray, because he had such a remarkably loose style, and he already had the basic idea of a rag doll for me to work with. Luckily this was also well before graphics started to turn over faster and faster, so I had a fair amount of time to work on the graphics, make a bunch of mistakes in the process to learn from, and hone in on the concepts before doing the final illustrations.

V: You entered the 1990s just as skateboarding was going through massive changes. How did that transition feel moving from Powell Peralta to World Industries?

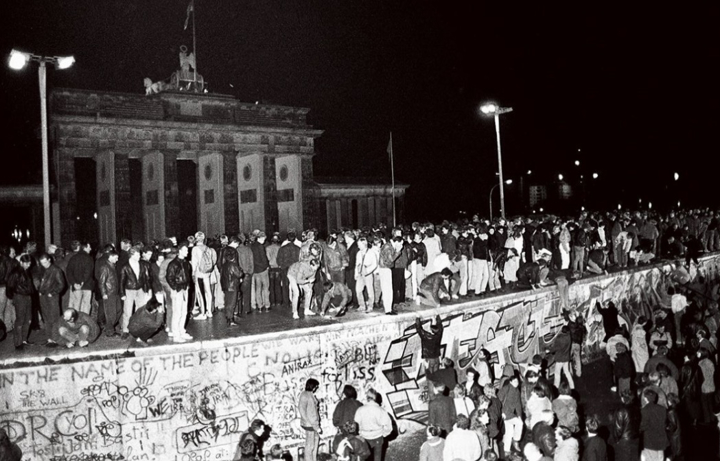

S: Well, I didn’t really make a smooth transition from Powell to World. My final year at Powell was a very frustrating one, because I was still actively out in the streets skateboarding and I was seeing the changes taking place firsthand, how Powell looked like a joke as it failed to compete with the likes of World, Blind, 101, H-Street, New Deal, Real, and all the other smaller, nimbler “skater-owned” companies. So, I kind of became an annoyance in the company. George and I frequently argued over the graphic direction. He even lost his temper on me once over the Frankie Hill “Clint Eastwood” graphic, because he thought I was trying to get the company sued. Anyway, when the company underwent a mass lay-off of employees in November 1991, George cut me loose. Even though I should have seen it coming, it still caught me entirely by surprise. I was devastated. I thought I was going to have to move back to Wisconsin as a failure. Fortunately, Steve Rocco heard I got let go and called me up the next week to come work for him down at World Industries. I already loved everything that World had been doing—the ads, the graphics, the videos—so I immediately said yes. And whereas Powell was a very formal 9-to-5 company where you had to clock in and out, World was absolute chaos with no structure whatsoever. Anything could happen or be done at any moment, and it was totally fun. I could work whenever I wanted, I could go skate whenever I wanted to. Rocco would even come to work and tell us the waves were good down at the ocean and we’d all go out on his boat or go jet skiing together. This kind of freedom inspired me to work even harder and for more hours. The concept of weekends ceased to exist. Marc McKee and I would often work 12 or more hours a day, and I think we both pushed each other to do better and better graphics, learning from each other and vibing off the energy.

V: The World Industries era is often described as a time of anarchy and innovation. How would you personally describe that environment under Steve Rocco?

S: When I started at World, Rocco made it known that he wanted the best skateboard graphics, and he would pay whatever it took to get them. So yes, the creative liberation was intoxicating. You wanted to make Rocco stoked. Above all, he was just like a big kid who wanted to have fun and make things hot. Powell had been all about production calendars and marketing schedules where it often took months before a new product was released, but at World, if Rocco suddenly had a graphic he wanted to do, the boards could be in shops within just two weeks. It was an exhilarating environment to work in.

V: Many of the graphics from that period were provocative, offensive, or downright hilarious. Were you actively trying to push boundaries, or were you simply reflecting the culture around you?

S: I think we were all just living in the moment. Skateboarding had lost all its popularity coming out of the 80s, the entire industry had turned upside down. A lot of what we were doing just happened to be what would make us laugh. At the time, shocking stuff was just funny, seeing what could be gotten away with, and at World Industries that was a lot—the one thing Rocco hated more than anything else was someone telling him that, no, he couldn’t do something. We all fed off that energy, and that’s exactly how Big Brother magazine began: TransWorld Skateboarding denied one of his ads, so he said, fuck this, fuck you, and started his own magazine where he could do anything he wanted.

V: What's the most chaotic thing that happened while you were working with Steve Rocco?

S: Probably the day at the office when he wanted to do an article in Big Brother called “Ho Spotlight,” a parody of TransWorld’s “Pro Spotlight,” and interview some strippers. So, he hired a couple girls to come to the office one afternoon and they did their stripper business right in the middle of Rodney Mullen’s office with several of the underage pro and amateur skaters lining the room. Even the UPS man was there watching! After the girls were done stripping, Rocco and Rodney tried to interview them but I don’t think they said anything all that interesting and we never ran the article. Plus, all the skaters freaked out about the photos that had been taken of them with the strippers—no one wanted their parents to find out—so they stole all the 35mm slides out of the Big Brother office.

V: Looking back, what do you think made that decade so special for skateboard graphics? Was it the humor, the freedom, or the total lack of rules?

S: All of it, really, but again, skateboarding was so small and tight knit then that everything flew under the mainstream radar. Plus, Rocco had set a high bar for graphics and every company tried to meet it in their own way. Once skateboarding gained in popularity in the late 90s, though, companies weren’t always able to get away with the crazier graphics they once did. Parents started buying boards for their children again and if they walked into a shop and saw some offensive graphics on the wall, they’d usually raise hell with the owner and cause problems. So, the skate shops started having a lot more influence in what they would or would not buy from companies, and that eventually led to the worst thing to ever happen to skate graphics: company logo boards.

V: If you had to pick one or two graphics that best capture the spirit of the 90s, which would they be and why?

S: I’d have to go with the Blind Jason Lee “American Icons” and the Real Jim Thiebaud “Hanging Klansman.” It was the point when satire and social commentary entered skateboarding, elevating the graphics beyond mere silly stuff like skulls, dragons, and other Dungeons & Dragons type stuff. These were fresh, new concepts that revolutionized the approach to skateboard graphics and I think that’s why specific ones still resonate so much from that period.

V: What was your motivation behind starting StrangeLove Skateboards? Was it partly a reaction to how artists are treated within the skate industry?

S: Partly, yes, because I’d been freelancing for a few years, and it was troubling how little many companies would pay for graphics. I was also hearing similar horror stories from other artists who were struggling and waiting on companies to cut and send out checks. Meanwhile, graphics of mine from over 25 years ago were still being reissued and produced and I never saw a single dime. Eventually it got so bad that I was having panic attacks while contemplating the prospect of reaching out to a few friends to see if I could possibly get a job in their shipping departments, because I wasn’t sure how long I was going to be able to make ends meet as an artist anymore. Fortunately, I had a friend, Nick Halkias, who loved the same era of skateboard graphics that I did, and we decided to start a company based on those irreverent ideals but also with the intent to treat our artist friends with more respect. If a graphic of theirs was successful, we would pay them more money with the additional runs. They would also retain ownership rights to their art once we stopped producing the graphics. All pretty high ideals, I guess, but we didn’t have any additional backers financing our shenanigans. It was just me, Nick, a credit card, and a bunch of ideas we’d always wanted to do with no one to tell us no.

V: StrangeLove’s visual identity feels playful, subversive, and deeply personal. How do you keep that energy alive while also running a legitimate business?

S: Well, honestly, it’s become increasingly harder to do so after the last few abysmal years for the skateboard industry. Coming out of the post-Covid euphoria really messed things up for everyone, from the shops to the companies and the manufacturers. Things have been tough for everyone. Fortunately, we’re still a super small company, don’t really have any employees to speak of, and we’re able to adjust to changes in the marketplace quickly. I do make things particularly hard on myself, though, because I don’t want to slap just anything on the bottom of a skateboard. I never wanted to make catalog filler, because what’s the point of that? It does nothing at all for the culture. But I also never wanted to be perceived as just an “art company” where people only buy the boards from us as wallhangers… that’s been exceptionally frustrating. It’s a perception in the marketplace we’ve had an incredibly hard time shaking. Not that it’s entirely our fault either, because aside from logo boards, I think one of the worst things companies have ever done is to purposely market boards—especially screen printed boards, something we regularly do—as being “limited edition” items, preying on the collector mentality and catering to resale vultures. It’s perverted the true meaning of what a skateboard is, and I think a few companies and collectors are paying the price for that now or will be very soon.

V: When you see the “board wall” today in skate shops, how do you feel about the state of skateboard graphics? Are things too safe—or just different?

S: Skateboarding has always been an evolutionary work in progress and the same thing applies to graphics. To the newer generations of skaters who have no relation to what skateboarding once was to us “old heads” over 30 years ago, this is their time. This is what they know. This is what they’re creating. It may not exactly be what I like, but it’s not supposed to be, either. It’s not being made for middle-aged adults. That said, when I do look at the board wall of a shop, I miss being able to differentiate one company from the other. So many of the graphics look similar from brand to brand now that the company identities get lost as they play “follow the leader” when a certain trend or look sticks—especially in the more “boutique” skate shops where the wall appears to be entirely comprised of one company. Sure, the standout graphics feel fewer and far between, but I’m also heavily biased and drawn to a different era and look. There’s always amazing stuff being created; you just have to sift through a lot more “commodity items” to find the gems.

V: Do you think the kind of creative freedom you had in the 90s could exist again today, in the age of social media and corporate branding?

S: No, not really. It’s almost impossible to stay off or even under the radar anymore. And you certainly couldn’t have a magazine like Big Brother anymore. I also think people have lost the ability to understand satire and sarcasm, failing to understand the context or meaning behind an image. This isn’t to say things can’t still be done… we created a StrangeLove “secret club” for this very reason, circumventing social media altogether.

V: What advice would you give to younger artists who want to build a career in skateboard graphics now?

S: Not to sell yourself short. I know everyone just wants to see their art on the bottom of a skateboard, but if you’re looking for an actual career and start out doing work for little or no money at all on a bro handshake, the companies will never respect you and it just makes things harder for every other artist trying to maintain a career. Also, have a contract in place stipulating how the work may be used and for how long. Are you giving them all usage rights? What happens when you’re in a toy store one day and see your work licensed out on a Tech Deck fingerboard? Just remember there’s nothing wrong with wanting to be treated like a professional, even if the industry is accepted for being notoriously unprofessional.

V: If you had to answer in one sentence: What does skateboarding mean to you, and what does graphic art mean to you now?

S: It may sound corny, but skateboarding has always been about landing that one next trick or achieving something that’s never been done before. I guess that’s how I still approach skateboard graphics, too, and still get excited by the prospect of nailing an NBD. Okay, sorry, that was two sentences, but I’m not really known for saying anything in a single sentence… just take a look at the blog on StrangeLoveSkateboards.com (strangeloveskateboards.com)!

Sean Cliver

@seancliver

Sean Cliver is an American skateboard artist whose career began at Powell Peralta, later moving on to shape the visual identity of World Industries. Known for some of the most influential and provocative graphics in skateboarding history, he now runs StrangeLove Skateboards, continuing to push forward the spirit and originality of skate art.